DISCLOSURE: Sourced from Russian government funded media

Written by Mikaprok. Translated by AlexD exclusively for SouthFront

“History in the subjunctive moods”

We continue our perpetual cycle with which we deconstruct contemporary politics with ironic transhumanism.

Let’s try to imagine how a true humanist should relate to what is happening in the world today.

We have an example to follow – the world-famous ventriloquist Yuval Harari. The author of several high-profile bestsellers, lauded by the international press and lambasted by (behind the scenes) international academic critics.

He is a renowned historian of the Middle Ages by basic education, knowing all about the knights of the Round Table, honor and duels. From the 15th century onwards, if not earlier.

In recent years, probably drawing on the rich material of the works of Walter Scott and Tobias Smollett, he has switched to predicting what the next 50-100 years have in store for us. Makes sense.

Department colleagues were confused. However, this is nothing new – popularity is not something to be thrown around. It is better to move on to new heights.

Mr. Harari, from the heights of authoring “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humanity” has lately also taken on the role of the columnist. He does this seldom but neatly.

Chronologically, the latter inclusion referred to the situation around the well-known EasternTyranny and the Solar Democracy bordering it in Southwest Eurasia.

The task looks daunting and may seem rather boring, but we will try to comment on the whole text of this heart-breaking manifesto of 9 February.

We leave the main text in the language of the publication in “The Economist”.

The subtitle – “Humanity’s greatest political achievement has been the decline of war. That is now in jeopardy”, – speaks to both the underlying meaning and a single thought construct for the whole material.

So, let’s read line by line:

At the heart of the Ukraine crisis lies a fundamental question about the nature of history and the nature of humanity: is change possible?

The upper register is taken right from the start. “Centuries of history are looking back at us from Khreshchaty”. A crucial question awaits an answer: will the Slavs live again in a nation-state or will they proceed peacefully to scrappage? The dilemma.

Can humans change the way they behave, or does history repeat itself endlessly, with humans forever condemned to re-enact past tragedies without changing anything except the décor?

One school of thought firmly denies the possibility of change. It argues that the world is a jungle, that the strong prey upon the weak, and that the only thing preventing one country from wolfing down another is military force. This is how it always was, and this is how it always will be. Those who don’t believe in the law of the jungle are not just deluding themselves, but are putting their very existence at risk. They will not survive long.

It wouldn’t be a bad idea to call these mysterious “schools of thought” something. For example, conservatism and liberalism. Not necessarily so, but it’s still not clear how they differ apart from this nuance.

However, the definition of the word “jungle” in this context implies only direct physical violence. It can also be covert. Say, some circumstances do not involve war but can provoke it by a specially organized set of circumstances. Then it is no longer a wild jungle, but a civilized conversation.

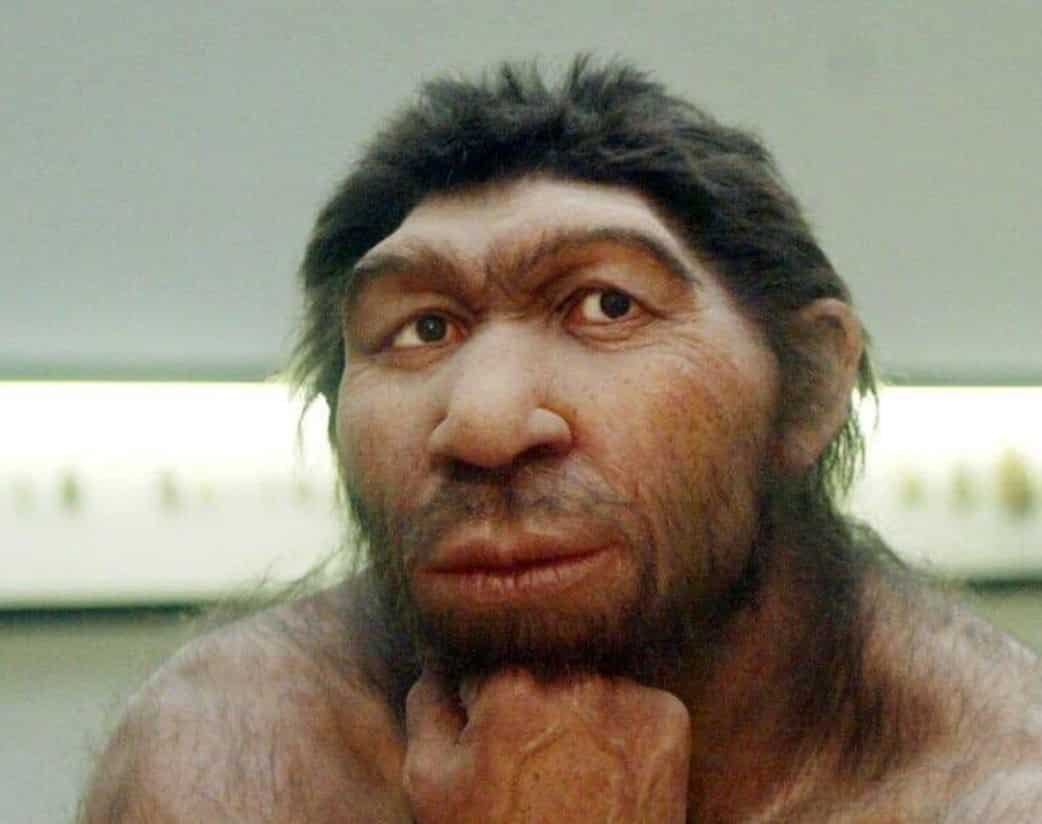

Another school of thought argues that the so-called law of the jungle isn’t a natural law at all. Humans made it, and humans can change it. Contrary to popular misconceptions, the first clear evidence for organized warfare appears in the archaeological record only 13,000 years ago. Even after that date, there have been many periods devoid of archaeological evidence for war. Unlike gravity, war isn’t a fundamental force of nature. Its intensity and existence depend on underlying technological, economic, and cultural factors. As these factors change, so does war.

Hmm, many anthropologists, as well as ethnologists, would disagree with such an audacious statement. Obviously, references to the scientific basis would have been useful here, but they are unfortunately not given.

Evidence of such change is all around us. Over the past few generations, nuclear weapons have turned war between superpowers into a mad act of collective suicide, forcing the most powerful nations on Earth to find less violent ways to resolve conflict. Whereas great-power wars, such as the second Punic war or the second world war, have been a salient feature for much of history, in the past seven decades there has been no direct war between superpowers.

It is convincing to take evidence from history in broad strokes, without detail. The article does have volume, but the Second Punic War cannot be forgotten.

During the same period, the global economy has been transformed from one based on materials to one based on knowledge.

Curious. Is it to be understood that it was the pursuit of knowledge that led Allied troops into Syria and Libya (for example)? Or, say the PRC has more knowledge potential than the Unites States – hence the conflict with the “world factory”.

Where once the main sources of wealth were material assets such as gold mines, wheat fields and oil wells, today the main source of wealth is knowledge. And whereas you can seize oil fields by force, you cannot acquire knowledge that way. The profitability of conquest has declined as a result.

In knowledge, nothing depends on industrial (variant: nuclear) espionage with the use of violence. Everything is freely available, take Wikipedia, for example. That’s from whom we need to learn.

Finally, a tectonic shift has taken place in global culture. Many elites in history — Hun chieftains, Viking jarls, and Roman patricians, for example — viewed war positively. Rulers from Sargon the Great to Benito Mussolini sought to immortalize themselves by conquest (and artists such as Homer and Shakespeare happily obliged such fancies). Other elites, such as the Christian church, viewed war as evil but inevitable.

In the past few generations, however, for the first time in history, the world became dominated by elites who see war as both evil and avoidable.

A generation is what, 25 or 50 years? So, to determine how to fit into the UN’s “several generations”.

Even the likes of George W. Bush and Donald Trump, not to mention the Merkels and Arderns of the world, are very different types of politicians than Attila the Hun or Alaric the Goth.

The very definition of politics has changed, hasn’t it? Alaric or Attila are slightly different in the functionality attached to their positions from Bush Jr or Trump. Not to mention Ms Merkel. We can compare them, no problem, but what will it ultimately do for us?

They usually come to power with dreams of domestic reforms rather than foreign conquests.

Hmm, if we’re talking about modern American leaders, that’s a stretch. What public agenda they come up with is not that important.

While in the realm of art and thought, most of the leading lights — from Pablo Picasso to Stanley Kubrick — are better known for depicting the senseless horrors of combat than for glorifying its architects.

Art is eternal, but not always humane.

As a result of all these changes, most governments stopped seeing wars of aggression as an acceptable tool to advance their interests, and most nations stopped fantasizing about conquering and annexing their neighbors.

Here again, we are faced with a difference in definitions. For a professional historian, it does not look too neat. Let us first define what war is and how it is viewed by contemporary theorists (see the same Yu. Harari “The Ultimate Experience: Battlefield Revelations and the Making of Modern War Culture”).

It is simply not true that military force alone prevents Brazil from conquering Uruguay or prevents Spain from invading Morocco.

Of course. But this did not happen even in the days of Attila and Alaric.

The decline of war is evident in numerous statistics. Since 1945, it has become relatively rare for international borders to be redrawn by foreign invasion, and not a single internationally recognized country has been completely wiped off the map by external conquest. There has been no shortage of other types of conflicts, such as civil wars and insurgencies. But even when taking all types of conflict into account, in the first two decades of the 21st-century human violence has killed fewer people than suicide, car accidents, or obesity-related diseases. Gunpowder has become less lethal than sugar.

Interesting, but we can talk about the sugar wars. For that matter, and appropriate excise taxes on products containing it.

Scholars argue back and forth about the exact statistics, but it is important to look beyond the maths. The decline of war has been a psychological as well as a statistical phenomenon.

And what about statistics?

Its most important feature has been a major change in the very meaning of the term “peace”. For most of the historic peace meant only “the temporary absence of war”. When people in 1913 said that there was peace between France and Germany, they meant that the French and German armies were not clashing directly, but everybody knew that a war between them might nevertheless erupt at any moment.

Not quite accurate, there were trade wars and there were alliance relations.

In recent decades “peace” has come to mean “the implausibility of war”. For many countries, being invaded and conquered by their neighbors has become almost inconceivable. I live in the Middle East, so I know perfectly well that there are exceptions to these trends. But recognizing the trends is at least as important as being able to point out the exceptions.

Is there such a definition as “implausibility of military coups”?

The “new peace” hasn’t been a statistical fluke or hippie fantasy. It has been reflected most clearly in coldly-calculated budgets. In recent decades governments around the world have felt safe enough to spend an average of only about 6.5% of their budgets on their armed forces, while spending far more on education, health care, and welfare.

With known exceptions and given the commercialization of military agency developments.

We tend to take it for granted, but it is an astonishing novelty in human history. For thousands of years, military expenditure was by far the biggest item on the budget of every prince, khan, sultan and emperor. They hardly spent a penny on education or medical help for the masses.

Yes, given the recent emergence of mass societies as such.

The decline of war didn’t result from a divine miracle or from a change in the laws of nature. It resulted from humans making better choices. It is arguably the greatest political and moral achievement of modern civilization. Unfortunately, the fact that it stems from human choice also means that it is reversible.

So there is a culture, but it only works on “good” people? Then it makes sense to decide on whom it should act.

Technology, economics, and culture continue to change. The rise of cyber weapons, AI-driven economies, and newly militaristic cultures could result in a new era of war, worse than anything we have seen before. To enjoy peace, we need almost everyone to make good choices. By contrast, a poor choice by just one side can lead to war.

That’s a shame. One madman for some reason can send all achievements of civilization back to Attila and Alaric. There seems to be an underlying social Darwinism in this everyday message.

By the way, why are new ways of war bound to be less deadly for long periods of time?

This is why the Russian threat to invade Ukraine should concern every person on Earth.

If it again becomes normative for powerful countries to wolf down their weaker neighbors, it would affect the way people all over the world feel and behave.

The key point of the story is to be silent hostage to the political situation and the consensus of the “peace-loving neighbors” regardless of their intentions. Even if one’s hands are tied and one is walking through a closed labyrinth, where decisions are made by civilized helpers.

The first and most obvious result of a return to the law of the jungle would be a sharp increase in military spending at the expense of everything else. The money that should go to teachers, nurses and social workers would instead go-to tanks, missiles and cyber weapons.

This is J.S. Mill’s key argument. There are dozens of answers, but for the sake of brevity: money can be printed, but people cannot yet be.

A return to the jungle would also undermine global cooperation on problems such as preventing catastrophic climate change or regulating disruptive technologies such as artificial intelligence and genetic engineering.

Of course, no one wants war, as well as getting back into the jungle. It is just that all territories have to be involved in the process of abandoning ambitions. Is it possible to say that the current US military budget looks effective with respect to addressing global warming?

It isn’t easy to work alongside countries that are preparing to eliminate you. And as both climate change and an AI arms race accelerate, the threat of armed conflict will only increase further, closing a vicious circle that may well doom our species.

It is even more difficult to work with countries that are destroying the population of your cultural area. The author of the bold assertion is invited to do a little work with his colleagues in the Gaza Strip.

If you believe that historic change is impossible and that humanity never left the jungle and never will, the only choice left is whether to play the part of predator or prey. Given such a choice, most leaders would prefer to go down in history as alpha predators and add their names to the grim list of conquerors that unfortunate pupils are condemned to memorize for their history exams.

But what lessons does the history of the “alpha predators” teach us? Do they always end badly?

But maybe change is possible? Maybe the law of the jungle is a choice rather than an inevitability? If so, any leader who chooses to conquer a neighbor will get a special place in humanity’s memory, far worse than your run-of-the-mill Tamerlane. He will go down in history as the man who ruined our greatest achievement. Just when we thought we were out of the jungle, he pulled us back in.

Someone is routinely compared to Tamerlane’s Mongols, but after all Mr “Harari” comes from Poland, which suffered greatly from the invasion of the Tatar Mongols. It’s a pity it has to be this way.

I don’t know what will happen in Ukraine. But as a historian, I do believe in the possibility of change. I don’t think this is naivety — it’s realism. The only constant of human history is change.

If this is the only constant, what is the science of “history” based on then? How do we test the hypothesis of super-AI and humanism? What can we expect from communities if they mutate endlessly, but a lousy sheep is found? It is not clear.

And that’s something that perhaps we can learn from the Ukrainians. For many generations, Ukrainians knew little but tyranny and violence.

The historical context is guessed according to the Polish trace.

They endured two centuries of tsarist autocracy (which finally collapsed amidst the cataclysm of the first world war). A brief attempt at independence was quickly crushed by the Red Army that re-established Russian rule.

The Soviet textbook organically merged in ecstasy with Russian and Ukrainian.

Ukrainians then lived through the terrible man-made famine of the Holodomor, Stalinist terror, Nazi occupation and decades of soul-crushing Communist dictatorship. When the Soviet Union collapsed, history seemed to guarantee that Ukrainians would again go down the path of brutal tyranny — what else did they know?

What does this have to do with Russian history?

But they chose differently. Despite the history, despite grinding poverty and despite seemingly insurmountable obstacles, Ukrainians established a democracy. In Ukraine, unlike in Russia and Belarus, opposition candidates repeatedly replaced incumbents.

Definitions again. The historian would do well to understand the basics of what is called democracy, what it is and why the Great French Revolution, which elected its leaders by the general assembly of citizens, is not particularly democratic in relation to those who are not members of the general assembly.

When faced with the threat of autocracy in 2004 and 2013, Ukrainians twice rose in revolt to defend their freedom.

In 2013, it is already possible to talk about a new chronology, and from whom did they save themselves in 2004?

Their democracy is a new thing. So is the “new peace”. Both are fragile, and may not last long. But both are possible and may strike deep roots. Every old thing was once new. It all comes down to human choices.

Always changing and being new is a good strategy for old and unchanging partners. The only constant is the change of others.

Wonderful material from an experienced author.

The last but important question remains: so many wise words were written by a well-known futurist from Israel, but for some reason, he did not reveal an important topic at all – where is the apologetics of a small but struggling Palestinian people for their own democracy? Why are their attempts futile and not supported by international forces of good?

Probably their suffering is not the defining moment of history.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy

Abundance soothes the wild beast. Kind of. Before the age of guns, violence was not so easy an option. Knowledge was the currency that initiated trade of other goods, and the type of knowledge shared was often an indication of intent and trustability. Knowledge of the cyclical way of things, and the process of identifying cycles by observing human nature spread across the earth. With modern religion and guns, this came to a halt, and was sent into reverse. The “time of the small” washed over the earth, and all things small were valued. Where now we turn to satellites and telescopes, instead of micro-scopes, we will once again, view and value the larger greater things of our reality. Choosing good leadership, is much easier if using knowledge of the cycles. Religion only seeks to feed itself, quite selfishly.

Comments are closed.