By Paul Fitzgerald and Elizabeth Gould

Table of Contents

Page 2: Overview of how JFK’s Plan for World Peace will be activated

Page 3: Chapter 1 The Fitzgerald Myth and History embodied in JFK’s life and Death

Page 6: Chapter 2 Our HAIR musical experience and why it still matters today

Page 10: Chapter 3 How the Mysticism of Newgrange pulled us into its vortex

Page 15: Chapter 4 Bhadshah Khan’s Afghan World Peace Movement

Page 20: Chapter 5 How JFK’s Plan for World Peace came to be

Page 23: Chapter 6 Passages from JFK’s Peace Speech resonate with Badshah Khan’s message

Page 25: Chapter 7 In order to turn from War to Peace, the Hegelian Dialectic must be dismantled

Page 27: Guest Chapter 1 Sima Wali (4/7/1951 – 9/22/2017), one of the foremost Afghan human rights advocates in the world

Page 33: Guest Chapter 2 A Nature-Based Perspective on Peace by Four Arrows aka Don Trent Jacobs, Ph.D., Ed.D.

Page 36: Guest Chapter 3 The Marriage of World Peace and Economic Justice Will Create Heaven on Earth. Peace must replace war as the foundation of life and Economic justice will lead the way to peace. (The economics of Henry George, a six-minute video on land value tax can be viewed here)

Page 40: Guest Chapter 4 A Brief History of How We Lost the Commons by Jay Walljasper

Overview of how JFK’s Plan for World Peace will be activated

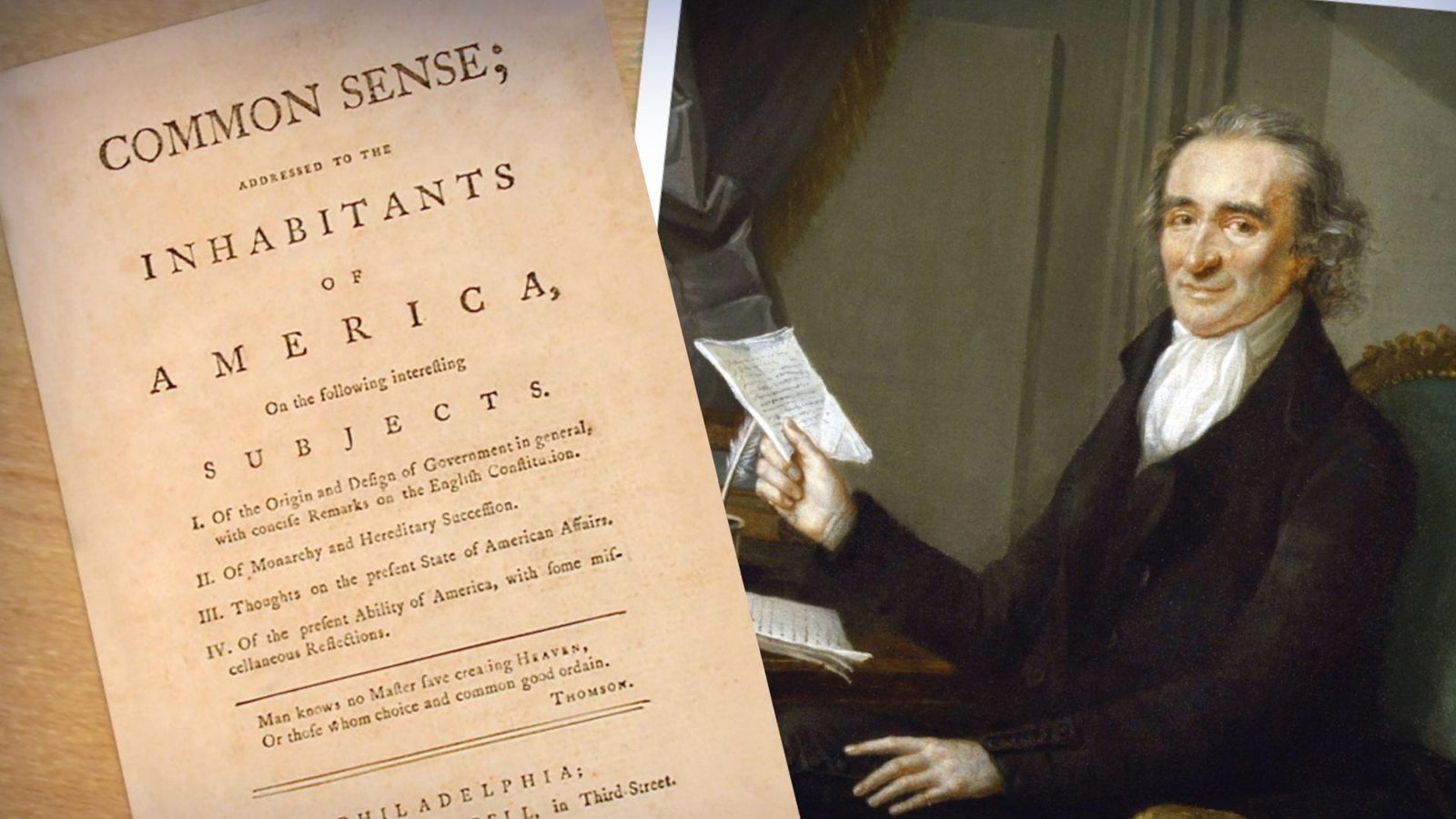

Violence begets violence, war begets more wars. These facts have been known to generations before our time and we should not have to learn this horrible truth again. Events have been forgotten by history and covered up by administrations. Old anger and hatred have been instilled in new generations. We cannot continue in this manner and survive as a people. We must calm down, face the facts of where we have come from, and put our minds to diffusing the crisis and not making it worse. Is there a solution? YES, there is; knowledge, understanding, and the courage to face our past and vow to resolve it without violence or prejudice. Americans are in a unique position to help through John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s peace legacy enshrined in his 1963 American University Speech. Activating his plan will be a new Declaration of Human Rights for the 21st century that will lay the foundation for a peaceful world to emerge out of the final chaotic stage of empire.

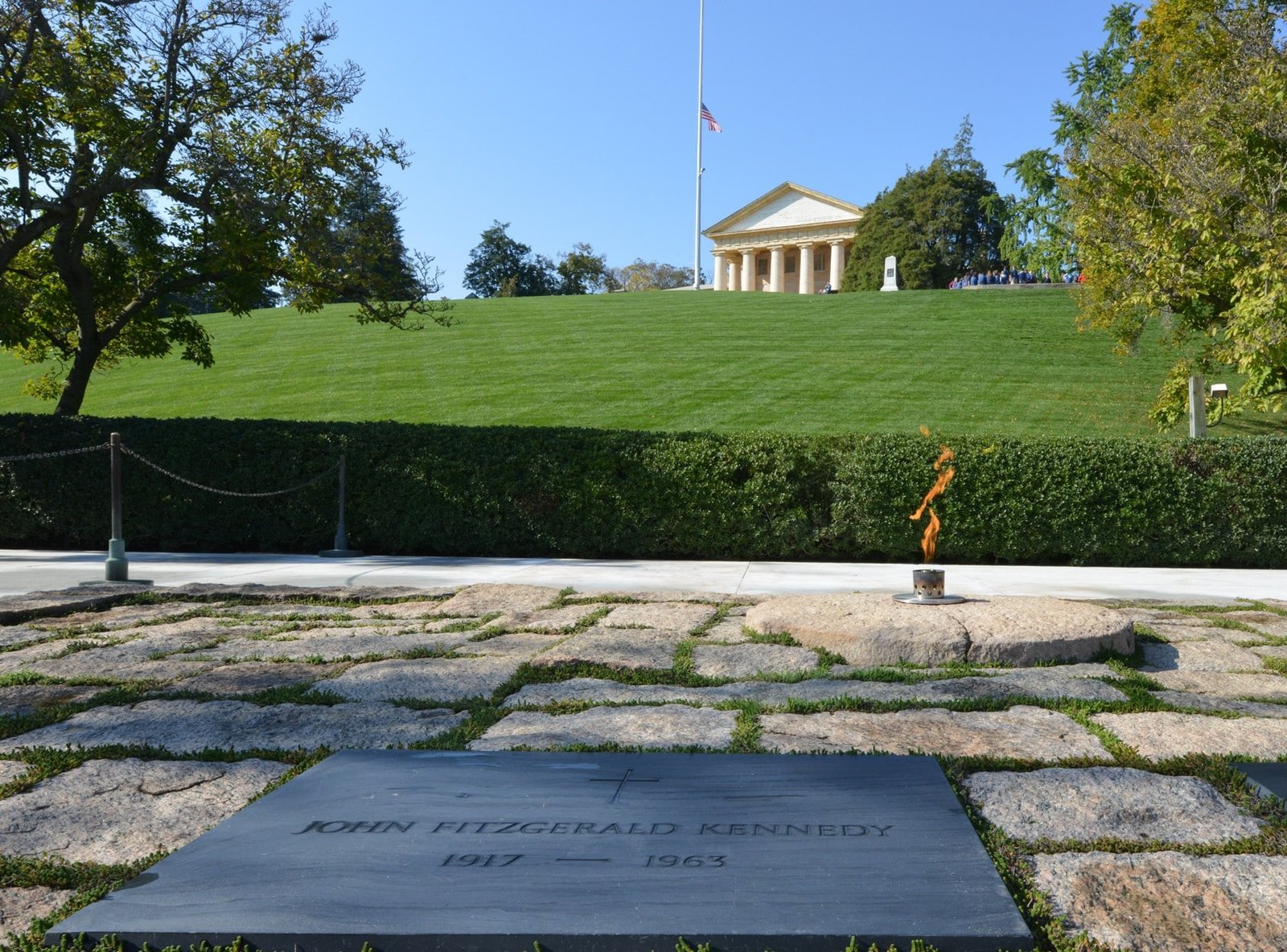

JFK is continually rated as one of our greatest presidents, a testament to his ability to inspire hope, faith, and courage in Americans. He asked us to take on the most important challenge of our times in 1963 by helping him to create world peace. His American University Speech laid out that plan with words that are powerful – so powerful he could have lost his life five months later just because of them. Resurrecting JFK’s plan for world peace is long overdue! We the People must do it. We the People can do it! We the people will do it! And the first step is for us, We the People to imagine the peaceful future we want, starting today.

Sharing positive ideas is not sufficient to change the world. We need to translate consciously the power of ideas into action. The first step is to unblock our feelings of fear and despair about the threats to our planet from the endless war agendas we face. Unlocking our creative power to imagine the peace we want will enable it to materialize as our future and once unlocked, the full potential for that future will provide the place for that peace to happen.

Next, we’ll intertwine JFK’s 1963 blueprint for world peace with Afghan tribal leader Bhadshah Khan’s indigenous non-violent movement known as the Khudai-Khidmatgar along a nature-based perspective on peace. Since there cannot be world peace without economic justice we’ll ground world peace in The economics of Henry George. Restructuring taxes so that land, a communal asset, is taxed instead of buildings on the land, has achieved sustainable prosperity for people all over the world. “The Georgist philosophy advocates equal rights for all and special privileges for none. It affirms a universal right for all to share in the gifts and opportunities provided by nature.” Ultimately when the marriage of world peace and economic justice is complete, it will create heaven on Earth.

Then we’ll include historical and mythical stories from the Fitzgerald family’s Irish roots. The finished plan would be delivered at a musical concert in Ireland and modeled after the 1985 Live Aid concert for famine relief in Africa. The sponsors of Live Aid took an issue nobody cared about, put it in front of 2 billion people through music, and raised $127 million. Unfortunately, not only are millions of lives still at risk today from famine in the third world, the first world is facing an unprecedented food crisis of its own. This exposes the truth that focusing on famine relief was never going to be a remedy for famine itself. Our concert will promote a genuine solution; establishing peace as the only underlying foundation that will address ALL human-made problems.

Our musical focus will be modeled after the wildly popular American Tribal Love-Rock Musical HAIR. In its time HAIR was the center of the Anti-Vietnam War Movement; delivering a riveting political and social awakening that we experienced personally in 1970 as participants in the Boston production of the show. HAIR’s finale song Flesh Failures Let the Sunshine In was an anthem for the worldwide peace movement; pleading with the audience to recognize with their hearts, that all people want peace and not war. It is a plea that still stirs the soul and will reenergize the movement we are building.

Our effort towards peace through economic justice, dialogue, and music will accomplish many things by breaking us free from the war dialectic of defeating the “other” and opening us to a self-aware perspective that can function as a spiritual and moral gauge for testing our own values. The concert will also be a re-awakening to bring back the peace robbed from our generation by dark forces manipulating from behind the scenes.

departure from the toxic war narrative is the only solution needed to totally change the tone and reorient people’s thinking from war to peace. This can be accomplished by connecting to our shared past through Ireland, the land that gave birth to the prophecy of the Fitzgerald family’s most beloved ancestor, Gearóid Iarla whom legend tells will rise from the dead at the end of time to free the Irish people from the tyranny of empire. The time is now for the fulfillment of that prophecy and we believe that can be accomplished by resurrecting JFK’s plan for world peace.

Finally, the perfect setting for a concert that will promote world peace through healing music is at a fifty-five hundred year old UNESCO World Heritage Site north of Dublin known as Newgrange or in Irish, Bru Oengusa. This legendary site is central to pre-Christian Irish mythology having been built by the Dagda, father of the Tuatha de Danaan, (people of the Sidhe the Shee). Known as the Good Father he was a benefactor to all the people. Described as a “passage grave” the Bru was a “house” where the dead could pass in and out of supernatural reality into this world at will. Most of all Newgrange will stimulate the imagination towards a deeper connection to the past and the evolution of human thought that has been forgotten to both the East and the West.

Chapter 1: The Fitzgerald Myth and History embodied in JFK’s life and death

Myths have been created by every culture worldwide for millennia. They are the stories of human encounters with the mystical handed down from one generation to the next. When myths are merged with the historical record the interaction aids in deciphering a more complex meaning of history. In our research into the Fitzgerald family’s rise and fall from power—starting with the 12th century Norman invasion of Ireland and ending four hundred years later with the beheading of the last earl of Desmond by Elizabeth I—we were faced with the limits of the historical record. Fortunately, the age of myth lived on in Ireland into the mid—20th century allowing us the ability to access a rich layer of meaning beyond history.

Starting with the Fitzgeralds’ arrival in Ireland in 1169 an outpouring of prophecies believed to be connected to the family was already in existence. Over time these prophecies became entwined with the prophetic legacies of Merlin, the Grail legends from Wales, the Irish prophets Moling, Brechan, Patrick, and Colmcille, and the ancient Irish legends of Finn and the Dagda.

The myths about the Earls of Desmond began to form in the early 14th century. Maurice Fitzgerald’s son Gerald, known as Gearoid Iarla in Gaelic, inspired the origin myth of the family. Born in 1338, Gearoid succeeded to the Earldom in 1358 making him the 3rd Earl of Desmond and the leader of the Munster branch of the Fitzgeralds—the most powerful Norman family in late medieval Ireland. Gearoid’s castle at Lough Gur, Co. Limerick became the center of the earldom and a home for his love of Gaelic culture. As a highly respected composer of Gaelic love poetry, Gearoid became a leading example of the Norman lords’ willingness to embrace their own Gaelicization. “More Irish than Irish themselves” was a phrase used by later historians to describe this phenomenon of total cultural assimilation.

The Fitzgeralds, as the new Norman overlords of Munster, adopted the mythic symbolism of the Gaelic tradition and embraced Aine as their goddess of Munster sovereignty. A poet in their employ in the 14th century referred to Gearoid’s father, Maurice as “Aine’s king” and Gearoid as “the son of Aine’s knight.” According to the folklore, Maurice was walking by the shore of Lough Gur when he saw Aine bathing, seized her cloak, which magically put her under his power, and then lay with her. Aine told Maurice that she would bear him a son Gearoid Iarla whom he was to bring up with the best of care. One caution she gave to Maurice; was not to show surprise at anything however strange his son should do because if Gearoid’s feats were recognized as magical he would have to go with his mother into the otherworld.

The boy grew into a handsome young man and one night there was a gathering at the castle with dancing. None of the ladies could compete with Gearoid but when one young woman rose and leaped over the guests, tables and dishes and then leaped back again the Old Earl grew concerned. “Can you do anything like that?” He said turning to his son. Gearoid then rose and leaped into a bottle and out again to the sound of great applause. But when the Old Earl looked with shock at his son’s performance, the evening came to an abrupt end.

“Were you not warned, said the young Earl, “never to show surprise at anything I might do? You have forced me to leave you.” And with those last words, Gearoid left the castle, entered the water of the river, and swam away in the form of a goose. The Old Earl’s display of surprise had forced his son to leave his father’s world.

The folklore concerning Gearoid continued to spread. During the 15th century, London grew nervous about the growing power of the Desmond earls and despite continued challenges, the Fitzgeralds’ prestige throughout Europe grew. The Gherardini, a powerful Florentine family claimed they were related. But tension reached a breaking point in the early 16th century as rumors spread that the Fitzgeralds were plotting to invade London and seize the power of the throne.

For over four hundred years the Fitzgeralds had been absorbed into the local mythology. Then in 1558, the 14th Earl of Desmond succeeded to the title. His name was Gerald, the first to have that name since Gearoid Iarla. The English deprived Gerald of his family estates by locking him up in London Tower for long periods of time. But rather than breaking his will, when Gerald returned home in 1573 he took on a stronger pro-Irish stance by joining his cousin’s rebellion against the English. Hopes ran high for the Fitzgerald campaign as the prophecies were circulated. In later folklore, it was claimed that the new Gearoid embodied the great Fitzgerald spirit of his 14th-century ancestor and that Gearoid Iarla had not died but returned at the hour of the family’s greatest need.

It is said that a man passing by Lough Gur saw a light and found the entrance to a cavern, where he saw an army of knights and horses asleep. There was a sword on the floor, and as the man drew it out the army awakened. Then its leader, Gearoid Iarla, asked if the time had come yet, but the man ran away. The army fell back to sleep, and the entrance could not be found later.

Although Gerald was an inspiration for Irish independence, by 1583 his cause was lost and he was killed. However, great affection for the family lived on, as did the hope that a Fitzgerald descendent would someday bring freedom to the land. There are repeated references to this mystical belief in documents from the 17th to the 19th centuries as well as London’s concern that the Fitzgerald’s defiance of English law and their embrace of Gaelic ways was an existential threat to London’s rule in Ireland.

Despite London’s fierce opposition, Gearoid Iarla and the myths surrounding him would continue to inspire future Fitzgeralds while winning the admiration of the Irish people. But as the power of these myths became entwined with Ireland’s 19th and 20th century politics, London’s fear of Irish independence brought on a new level of brutality that caused the Irish people to unite. To the royals, siding with the “people” over loyalty to the Crown was the highest treason of all. And when the Fitzgeralds’ identification with the people was transferred to the United States through JFK it became inevitable that the old forces aligned against his family would again rise to meet his challenge.

Chapter 2: Our HAIR musical experience and why it still matters today

Paul Fitzgerald as Claude at the Wilbur Theater in 1970, Boston Globe

We had done the research for an article on mind control that included the role of MK-ULTRA; a CIA project which operated from the early1950s through the 1960s had subjected Americans to mind-altering experiments without their consent. The project remained secret until 1975 when the Church Committee Hearings revealed the CIA’s illegal activities. But what really caught our attention was the confirmation that MK-ULTRA had infiltrated the Anti-Vietnam War Movement to undermine its legitimacy with the distribution of psychedelic drugs.

As teenagers growing up in the1960s the music scene and the antiwar movement were synonymous. A new age was dawning and our generation wanted to keep war from becoming part of it. What we didn’t know until recently was how much influence military intelligence and the CIA had in forming what we believed was an organic outgrowth of popular sentiment against the Vietnam War.

Before bands such as The Doors and The Byrds became famous; the songwriters, musicians, and singers who would form those bands flocked to Laurel Canyon. What was strange about this migration was the absence of a music industry in the area. What it did have was Vito Paulekas and the Freaks; a regular feature of the Sunset Boulevard Club scene starting in 1964. Paulekas was known for supplying wildly frenzied dancers to stir interest in the bands and is credited with their early success. Having materialized a musical revolution out of thin air, he has also been credited as the inspiration for the Hippie movement’s fashion and free love of the communal lifestyle.

Another oddity was that many of the artists who arrived were descended from influential families, and had military or intelligence backgrounds or connections to high-ranking military personnel. Frank Zappa, creator of The Mothers of Invention spent his youth at the Edgewood Arsenal Chemical Biological Center where his father was a chemical warfare specialist. Edgewood Arsenal was connected to MK-Ultra’s mind control program. Major Floyd Crosby, father of David Crosby of Crosby, Stills, and Nash was an Annapolis graduate and WWII military intelligence officer descended from the Van Rensselaers, a prominent American family.

Doors Keyboardist Ray Manzarek served in the highly selective Army Security Agency as an intelligence analyst in Laos in the run-up to the Vietnam War. Doors producer Paul Rothchild also served in the same Military Intelligence Corps in 1959. Jim Morrison was the son of U.S. Navy Admiral George Morrison.

In August of 1964, U.S. warships, under Morrison’s command, claimed to have been attacked while patrolling Vietnam’s Tonkin Gulf. Although the claim was false, it resulted in the U.S. Congress passing the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, which provided the pretext for an escalation of American involvement in Vietnam. Morrison never spoke publicly of his father’s role in creating the “false flag” that was used to deceive the American people into accepting a war against Vietnam.

More intriguing was Morrison’s lack of interest in music until he transformed into one of the most glorified rock stars of all time. As the Door’s lead singer, Morrison played a major role in forming the band’s identity. He chose its name from Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception. Huxley’s “doors” opened through the use of psychedelic drugs. He was also a key player behind the use of MK-Ultra’s research into mind control. In a 1949 letter to George Orwell, Huxley described psychedelic drugs as far more efficient than prisons.

As an acolyte of the Greek god Dionysus and the Dionysian Mysteries Morrison reveled in the use of drugs, drink and frenzied dancing. MKUltra’s objectives had much in common with the Dionysian Mysteries and Morrison’s philosophy of life who said “I believe in a long, prolonged, derangement of the senses in order to obtain the unknown.” Morrison was also described as a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Doors manager Paul Rothchild explained, “You never knew whether Jim would show up as the poetic scholar or the kamikaze drunk.

Americans need to look back and reconsider the turning points that brought our country to this crossroads. How did we come from being so much against the war in Vietnam to preparing for an endless war against everyone on the planet today? Was the Laurel Canyon scene the only operation sabotaging the legitimacy of the anti-war movement? Was the CIA responsible for permanently wrapping the anti-war movement and public dissent in a cloak of freaked-out hippies, communal sex, and acid trips on LSD?

The 1950s and 1960s saw America in direct competition with the Soviet Union, not only for military superiority but also for the world’s hearts and minds. The Cultural Cold War waged by Washington embraced activities that were intended to outshine its communist rival in literature, music, and the arts with a whole new way of engaging the world. A psychological warfare campaign to break down traditional patterns of behavior had already been laid out in 1953 by the CIA’s Psychological Strategy Board’s doctrine for social control known as PSB D-33/2. With an emphasis on the strange and avant-garde, the CIA began bringing artists, writers, and musicians into what was known as its “Freedom Manifesto.” The CIA came to view the program as a landmark in the Cold War, not just for solidifying its control over the non-communist left and the West’s intellectuals, but for enabling the CIA to secretly disenfranchise Europeans and Americans from their own political culture in such a way they would never know it.

As the historian of the CIA’s secret co-optation of America’s non-communist left Christopher Lasch wrote in 1969 “The modern state is an engine of propaganda, alternately manufacturing crises and claiming to be the only instrument that can effectively deal with them. This propaganda, in order to be successful, demands the cooperation of writers, teachers, and artists not as paid propagandists or state-censored time servers but as ‘free’ intellectuals capable of policing their own jurisdictions and of enforcing acceptable standards of responsibility within the various intellectual professions.”

While declaring itself as the antidote to communist totalitarianism, one CIA officer viewed PSB D-33/2 as interposing “a wide doctrinal system that accepts uniformity as a substitute for diversity,” embracing “all fields of human thought-all fields of intellectual interests, from anthropology and artistic creations to sociology and scientific methodology.” He concluded “That is just about as totalitarian as one can get.”

The evidence that the birth of the psychedelic 1960s New Age music scene was guided by the invisible hand of military and intelligence operatives is well documented. But what about the American Tribal Love-Rock Musical HAIR that swept the world in 1968 after opening to rave reviews on Broadway?

We lived our experience with HAIR when we became a part of the Boston production in 1970 while college students. HAIR was on the front lines of the anti-war movement and we waved the banner every night before sold-out audiences. To us, the Vietnam War was nothing more than what Daniel Ellsberg described as a neocolonial enterprise. America’s Winter Soldiers joined us on stage to celebrate our right to dramatize the undoing of American society by the terror being inflicted on Southeast Asia.

HAIR was a worldwide phenomenon with casts in every major U.S. city and nineteen productions outside North America. Its anti-war theme was shared by millions of Americans who watched and participated in it. Every HAIR cast was local to the city it performed in and established new standards for racial diversity unheard of at the time. HAIR made the war and its impact on human beings personal in ways that nothing else could.

But that impact and the anti-war momentum it had accrued was lost and channeled away from the universal peace we believed was possible. Was HAIR’s popularity part of a cultural cold war experiment to influence public opinion and then made to go away? A 1977 revival of HAIR at the Biltmore Theatre, where it ran for 1750 performances from 1968 to 1972, was surprisingly attacked by the NYT as too far gone to be timely; too recently gone to be even nostalgic.

With its antiwar message dismissed and President Carter’s Russo-phobic National Security Advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski taking over security policy at the White House, the message was clear. The antiwar movement would not be coming to power in Washington in 1977 and never would. When the film version of HAIR was released in 1979 – it was rewritten and detached from the show’s anti-war theme. With Vietnam disposed of; the West’s endless war against the Soviet Union could be put back on track. By the time Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980, the anti-Vietnam War movement had been reduced to a “Syndrome” and cured with a World War II size defense budget that transformed the U.S. from a creditor to a debtor nation.

The celebrity arm of the non-communist left was well represented at our 1970 HAIR opening night with the presence of Peter, Paul, and Mary’s Peter Yarrow and the show’s executive producer Bertrand Castelli; a member of Europe’s cultural cold war elite. Yarrow’s Ukrainian-born father, Bernard was a member of the CIA’s European cultural front organization the National Committee for a Free Europe. Having served during World War II in the OSS and then joining the Dulles brothers‘ law firm, Bernard helped found Radio Free Europe and became its senior vice president. Following Vietnam, Yarrow transferred his activism to Soviet Jewry and their emigration to Israel, a major component of the neoconservative agenda.

By the 1980s the issue became a key platform of the Reagan administration’s ability to stop détente with the Soviet Union. As for HAIR, stripped of its antiwar message, it was reduced to being the poster child of a 1960s debauched hedonism. Or as Castelli labelled a revival in 2008, “Everything that was joyful and harmless became dangerous and ugly.” Dangerous and ugly is not the way we remember our experience. Nuclear war and Vietnam were dangerous and ugly and in the intervening years that danger and ugliness returned to haunt us.

If HAIR was part of a psychological campaign to energize the youth of America to action in the pursuit of peace, freedom, and happiness it succeeded. But if the ultimate objective was to crush that freedom and numb us to the danger of permanent war it too succeeded. At the time, HAIR’s success helped us believe that we had changed our future for the better. The war ended and the troops came home, but we now accept that the new age we sought was nothing more than an illusion.

President Eisenhower warned what would happen if our country dedicated itself to war. Endless war puts you in a hell of madness from which there is no escape. The madness of war on the world has come full circle and is now in our schools, parks, bars, and homes. It was always there as part of our nature. We have given in to a part of our nature that should have matured and been processed but instead has remained aloof from our humanity. That part of our nature is still unlearned and untamed. We are the victims of our own design and therefore we can change it.

The CIA did succeed in redirecting Americans’ anti-war sentiment towards accepting permanent war. To paraphrase, Hermann Goering’s statement at his Nuremberg trial: People don’t want war, but people can be brought to the bidding of their leaders by instilling fear or denouncing the pacifists for exposing the country to danger and it works the same way in any country.

Our only course is to step outside today’s endless war narrative and see where we are in the paradigm. The false narratives that control our thinking will fall away as we replace them with deep knowledge and acceptance of what we have actually lived through. As the past finally becomes prologue; we can imagine the genuine future we truly want and start to make it happen.

We’ll end with a video of Paul Fitzgerald singing Flesh Failures Let the Sunshine In with the Boston Cast of HAIR at a performance given at Boston City Hospital in the summer of 1970. It was a cloudy afternoon when the cast started singing Let the Sunshine Shine In and the sun literally burst through the clouds as if on cue. Unknown to us at the time, the concert was filmed by the hospital’s mortician and magically found its way to us a decade later. Although the video is of rough quality, the healing tone generated by HAIR’s plea for peace still shines through.

Lyrics to Flesh Failures/Let the Sunshine In, the Anthem for the World Peace Concert

We starve-look at one another Short of breath

Walking proudly in our winter coats

Wearing smells from laboratories

Facing a dying nation

Of moving paper fantasy

Listening for the new told lies

With supreme visions of lonely tunes

Somewhere Inside something there is a rush of

Greatness who knows what stands in front of

Our lives I fashion my future on films in space

Silence Tells me secretly

Everything Everything

We starve-look At one another Short of breath

Walking proudly in our winter coats

Wearing smells from laboratories

Facing a dying nation Of moving paper fantasy

Listening for the new told lies

With supreme visions of lonely tunes Singing

Our space songs on a spider web sitar

Life is around you and in you

Answer for Timothy Leary, dearie

Let the sunshine Let the sunshine in, the sun shine in

Let the sunshine Let the sunshine in,the sun shine in

Let the sunshine Let the sunshine in,the sun shine in…

Chapter 3: How the Mysticism of Newgrange pulled us into its vortex

We were first brought into the mystical vortex of Newgrange, the ancient megalithic passage tomb on August 1, 1997 at Dublin airport when the young driver of the shuttle bus posed a question after reading the name tag on our luggage. “Who’s the Fitzgerald?”

“We are.” My son responded. “Well so am I.” He said.

That was the first hint that something unusual was happening on our visit to Ireland. In the old pagan Celtic calendar, August 1st was the Feast of Lughnasa in honor of the Irish god Lugh—brother of the Dagda – the chief god of the supernatural race known as the Tuatha de Dannan—And oddly enough Newgrange was his home.

The second hint came when I asked the young man where he came from. “Oh, it’s a little village down past Limerick. I’m sure you’ve never heard of it. It’s called Abbeyfeale.” “That is my grandfather’s village,” I told him. “We’re from the same place.” Was this coincidence, synchronicity, or something more?

“Well, whatever you do when you’re in Ireland.” He said. “There’s one place you must go. It’s called Newgrange, Bru Oengusa in Irish – Angus’s mansion on the river Boyne. I’d take you there myself, but I’ve got to work. It’s only a twenty-minute drive from where you’re headed and it is the most amazing thing you will ever see.”

I knew that returning to Ireland would complete something I’d started when I’d first visited there back in 1971. But it wasn’t until we were directed to Newgrange by another Fitzgerald from the same village as my family on the other side of Ireland did I realize—that something—was far more profound than anything I’d experienced in my lifetime.

Jung described the concept of synchronicity or coincidence as an “acausal connecting principle,” that joined the rational ego of the senses to the Daemonic ego of the irrational “other self” which then overlapped into our reality. The Daemon was well known to the ancient philosophers as the causer of Déjà vu—the feeling of having experienced a present moment once before. To the classical Greeks, it was a supernatural spirit guide who caused coincidences to happen in order to shape our destiny. Was this message from another Fitzgerald part of an acausal connection directing me to apply our six years of research on the Fitzgerald family to something at Newgrange?

Within a few days, we’d made our way to the Boyne valley and had to shield our eyes from the glare of the quartz crystals shining in the bright sunlight. The young Fitzgerald from Abbeyfeale had been more than right. From a distance, Newgrange looked like a giant-futuristic time machine. But as we soon learned that time machine hadn’t arrived from the future but had traveled five thousand years out of the past.

Originally built in the shape of an egg, its exterior was now a drum-shaped flying saucer with a facade covered by eleven feet of quartz that glowed like an ancient solar timepiece in the early morning sun. In fact, even after five thousand years it still kept perfect time by focusing an intense, almost laser-like light into the darkness of Bru Oengusa for exactly seventeen minutes every winter solstice. Wealthy Romans had once made pilgrimages to it from Britain and left precious offerings of gold and jewelry to propitiate the spirits of its powerful gods, the Tuatha de Danann. And it was suspected that large crowds of people had once filled its huge natural amphitheater to participate in a yearly ritual hinted at in ancient annals as involving music, magic, and “many colored Chequered Lights.”

Newgrange was older than the Temples of Mycenae and the Pyramids. But like the Pyramids, which appeared to have had some ceremonial function in addition to their role as tombs, what else did this quartz palace do? Was measuring the solstice the only reason its builders had labored for years to plot the exact movement of the sun? And why, over all the other sacred sites around the world did Joseph Campbell consider this place to be the home of the most sought-after of relics, the Holy Grail?

It wasn’t until we probed Campbell’s well-known book The Masks of God that pieces of the mystery of Angus’s mansion began to fall into place. “By various schools of modern scholarship,” Campbell wrote, “the Grail has been identified with the Dagda’s caldron of plenty, the begging bowl of the Buddha in which four bowls, from four quarters, were united, the Kaaba of the Great Mosque of Mecca, and the ultimate talismanic symbol of some sort of Gnostic-Manichean rite of spiritual initiation, practiced possibly by the Knights Templar.”

Limited to being a “passage tomb” by modern scholars, the mansion of Angus in Irish myth was described as a place where Angus could go to visit his dead friends making it quite literally a “house” where the dead could pass in and out of supernatural reality at will. It was also a place where the living could experience what awaited them in the spirit world beyond.

Having been carbon dated to at least 3500 BCE Bru Oengusa was far older than “Irish” or “Celtic” culture and is now thought by some to represent the zenith of a peaceful Golden Era of human existence that reached from Anatolia in the Near East across Europe into the heart of ancient Ireland. The Grail has been the object of occult quests for millennia as the divine chalice of “becoming.” And according to Joseph Campbell, Bru Oengusa represented the place where it could be found, making it a sacred domain suspended between the world of matter and the realm of pure spirit.

Campbell’s statement was a mythological Rosetta Stone, tying together a deep vein of mythology about the origins of human spiritual existence together with a little-understood prehistory of Europe. But as the poets and mythologists George Russell and W.B Yeats testified, it was also a metaphor for a transubstantiation of mind and matter from the irrational ego to the rational. To their minds, the egg-shaped mansion of Oengus was where the Dagda – the ancient father/Sun God of the Tuatha De Danann – impregnated matter with light and brought forth a race of invisible beings who are to this day regarded as operating behind the scenes.

So how did this dreamlike transformation from light to matter work? In 1897 George Russell, the mystic, poet, and prominent Gaelic Revivalist known by the initials A.E. visited Newgrange in the company of fellow mystic, William Butler Yeats. Russell left an account of the impression the monument made on him in his poem A Dream of Angus Og:

“As he spoke, he paused before a great mound grown over with trees, and around it silver clear in the moonlight were immense stones piled, the remains of an original circle, and there was a dark, low, narrow entrance leading therein. “This was my palace. In days past many a one plucked here the purple flower of magic and the fruit of the tree of life…

“And even as he spoke, a light began to glow and to pervade the cave, and to obliterate the stone walls and the antique hieroglyphics engraved thereon, and to melt the earthen floor into itself like a fiery sun suddenly uprisen within the world, and there was everywhere a wandering ecstasy of sound: light and sound were one; the light had a voice, and the music hung glittering in the air…

“I am Aengus; men call me the Young. I am the sunlight in the heart, the moonlight in the mind; I am the light at the end of every dream, the voice forever calling to come away; I am desire beyond joy or tears. Come with me, come with me: I will make you immortal; for my palace opens into the Gardens of the Sun, and there are the fire fountains which quench the heart’s desire in rapture.” (AEON, A Dream of Angus Og, 1897)

The Boyne Valley monuments have played an important but little-known role in British politics. In the late 19th century, a fanatical group of British-Israelites excavated nearby at the ancient seat of Irish kings at Tara attempting to prove Britain’s descent from ancient Israel and the House of King David. Convinced the Ark of the Covenant was buried there, they found no Ark but did succeed in scattering five thousand years of ancient Irish history leaving Tara more a looted graveyard than a magical court of legendary heroes and kings.

After witnessing New Grange in all its shining quartz glory, it made us wonder whether this destruction was accidental or done intentionally to obscure its true history. But then we learned that the Newgrange of today is not the mansion of Angus it was when viewed by George Russel and William Butler Yeats under a full moon in 1897. Newgrange had been significantly altered in the 1960s to conform to the restorer’s “idea” of what it might have looked like some 5300 years ago – and not what it was carefully designed to do.

According to one of many critics who have studied the reconstruction, despite all the effort put into restoring Newgrange’s magnificent appearance, “It doesn’t work like it used to,” wrote Hugh Kearns, author of The Mysterious Chequered Lights of Newgrange. “And if it was made to work again, and it could, then the number of visitors would soon be back to the original Stone Age levels.”

As a modern Irish designer and engineer, Hugh Kearns believes that in addition to having had a ritual significance, Newgrange once functioned as a kind of light machine, capable – when constructed properly – of projecting images through the use of its “chequered lights.” To prove his theory he constructed a scale model that when tested worked to perfection. So if true, was Newgrange somehow used by ancient engineers to project the images of fallen heroes as recorded in the Irish annals? Was it really a place where Angus could go to visit his dead friends? Or, was Newgrange providing the power with its quartz crystals, solstice sun and musical tones to do something more? And was that something more, the power to access the inner workings of an organic otherworld hologram and not just its emulation?

Newgrange felt eerily familiar to us when we first saw it that day glistening in the sun. Its original purpose was clearly more than just as a burial mound and we soon learned that the origin mythology of the Fitzgerald family’s arrival in Ireland mirrored its origin mythology as well. The myths that had been applied to the chief god of the Tuatha De Danann, the Dagda, and his son Angus were applied to the Earl of Desmond and his son Geroid and remain alive to this day. The fact that we’d been directed there out of the blue by another Fitzgerald from my grandfather’s village qualified as genuine synchronicity (the so-called book falling off the shelf) and we were eventually to discover the legendary power of the family name possessed truly mythic qualities of its own.

“The family’s Irish myth-makers were capable of grafting the Geraldines onto a native historical tradition that traced their lineage back to the Greeks, while at other times and for different audiences, the family could make a plausible claim to an Italian and ultimately Trojan lineage,… The old adage that the Geraldines became ‘more Irish than the Irish themselves’ fails to capture the Geraldine experience in medieval Ireland in all its richness and variety.”’ Editors Peter Crooke and Sean Duffy wrote in the preface to their 2017 book, The Geraldines and Medieval Ireland, the Making of a Myth.

And so in writing our dream-inspired novel The Voice and our new book Valediction Resurrection, we found ourselves building on all the richness and variety of the mythology we could find. And ultimately we came to discover that the Fitzgerald myth was not only firmly grounded in reality but that the reality was firmly planted in an otherworld of dreams, synchronicities, and coincidence—and that those coincidences are caused by something known as the Daemon.

We made the decision to investigate the Fitzgerald family based on our daughter Alissa’s dream in 1991 in which Paul’s deceased father visited Alissa accompanied by an eight hundred-year-old man in a strange plaid suit. His message was clear. Fix the memory of the family. And so as we wrote our novel The Voice the mythology of Newgrange became incorporated into the story and as we worked toward a publishing date in 2001 the importance of Newgrange as a character became clear.

Following the publication of our two books on Afghanistan in 2009 and 2011 we began working with members of the Afghan diaspora on a peace conference and recommended Newgrange as a neutral location for the Afghan people to come together. Aside from sharing a long colonial heritage with Britain and Ireland, Afghanistan shared an ancient legacy of tribal law and secular codes of moral conduct that long preceded the Christian and Islamic eras. Ireland’s pre-Christian Brehon Laws provided a sophisticated set of rules for every aspect of Irish society. According to the legendary 19th-century British agent Alexander Burnes – Prior to hostile European invasions, Pashtunwali was a guide for a peaceful and hospitable Afghanistan that was known to accommodate Jews and Christians, considering them both to be religions of “the book.”

We believed a departure from the existing narrative was needed to change the tone of the Afghan crisis and reorient people’s thinking. As part of the indigenous solution to restore the true Afghanistan, Afghans needed to allow themselves an escape from the existing extremist narrative by reconnecting to an ancient shared past. We believed this could be achieved by holding initial planning sessions at Newgrange with Afghan leaders and organizations from around the world to share their knowledge as advisors and supporters. And this proposal was totally embraced by our Afghan partners. That dream of Afghan peace was never fulfilled.

We are resurrecting the concept centered on Newgrange as the location to inaugurate a Declaration of Human Rights for the 21st century World Peace as a musical concert.

Chapter 4: Bhadshah Khan’s Afghan World Peace Movement

Is not the Pashtun amenable to love and reason? He will go with you to hell if you can win his heart, but you cannot force him even to go to heaven – Badshah Khan

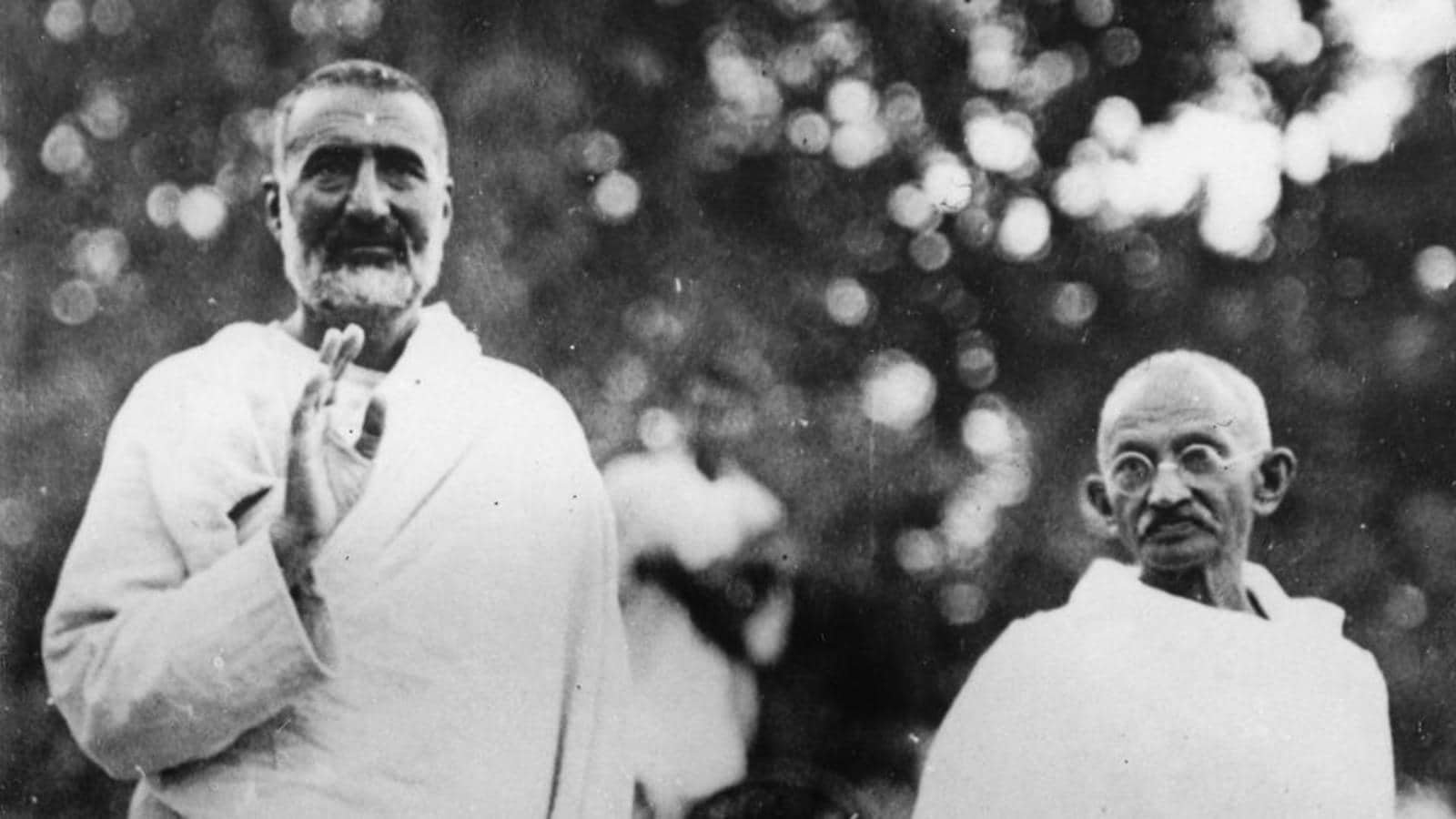

If anyone today could name a historical figure connected to the origin of non-violent resistance against political oppression, it would most likely be India’s, Mohandas Gandhi. Gandhi virtually defined the idea of non-violent resistance in his struggle to free India from British colonial rule.

But in 1929, a Pashtun tribal leader in nearby Afghanistan named Bhadshah Khan – a peer of Gandhi – became an important ally by inaugurating Afghanistan’s indigenous non-violent movement known as the Khudai-Khidmatgar – the servants of God. Since Khan realized that God needed no service he decided that by serving God they would in fact be serving humanity and set out to remove violence from their ancient Pashtun tribal code. Known as Pashtunwali, Afghans had lived by the code’s elaborate rules for millennia and continue to order their lives by it to this day.

In addition to establishing a leadership council accepted by the community, Pashtunwali laid out in detail the proper behavior for hospitality as well as what was necessary to create security for all including how and when the act of revenge was acceptable.

Following Britain’s colonization of Afghan tribal lands east of the Hindu Kush Mountains in 1848, these principles of Pashtun law were gradually replaced by a new British colonial order. Pashtun society was already known to be in need of social reform for its long-standing acceptance of revenge killing. But the British creation of a small, elite landlord class to control and administer the province turned revenge killing into a permanent blood bath.

According to Dr. Sruti Bala of the University of Amsterdam: “With traditional tribal authority diminished, this ruling elite gradually emerged as a group of powerful landlords who fought among each other and increased rivalry among the clans. By introducing their own manner of punishment and control, including fines, levies, and even imprisonment, they created a new culture of conflict with its own rules of the settlement.”

According to Bala “this was a major change in comparison with the tribal councils’ traditional focus on limiting conflicts and blame, and resolving feuds without punishment.” The 1872 Frontier Crimes Regulation Act further worsened the situation by sanctioning punishments and mass arrests without trial and legal support and placed heavy restrictions on the free assembly of ethnic Pashtuns. The Frontier Crimes Regulations were far stricter in the Pashtun territories than in any other part of British India and directly limited civil liberties. According to Bala, “The infringements on civil as well as basic human rights were legitimized by the apparent need to control the Western frontier as a defensive line against Russian aggression and military advances in the region.” And this was of course long before the threat of Soviet communism ever existed.

British competition with Russia for control of Central Asia was a central feature of 19th-century imperialism known as the Great Game. Over time a delicate balance was reached and Afghanistan was used as a buffer state between empires but not without a brutal suppression of the Pashtun tribes by the British.

Khan’s appeal to non-violence was accepted by many Pashtuns as a way to resolve deep-rooted social problems while undermining British authority at the same time. Although organized like an army, his recruits swore an oath to renounce violence and to never so much as touch a weapon. Over time, the Khudai-Khidmatgar movement developed an educational network to address the social and cultural reforms needed to leave revenge and retribution behind and move towards non-violent development.

This network served the community by focusing on education for all, encouraging poetry, music, and literature as avenues of expression that would help eradicate the roots of violence that had become normalized among Pashtuns during British rule.

The non-violence base of the Khudai-Khidmatgar not only addressed the imbalance created by tribal feuds, it also brought Afghans under the single platform of non-violence which ultimately helped the Pashtuns present a powerful united front against British imperial designs.

Khan was an active member of the Indian National Congress, Chief of the Frontier Province Chapter of the Congress, and a close ally of Gandhi and when they first met he questioned Gandhi about something that troubled him. “You have been preaching non-violence in India for a long time,” he said. “But I started teaching the Pashtuns non-violence only a short time ago, yet the Pashtuns seemed to have grasped the idea of non-violence much quicker and better than the Indians. How do you explain that?” To which Gandhi replied, “Non-violence is not for cowards. It is for the brave and for the courageous and the Pashtuns are brave and courageous. That is why the Pashtuns were able to remain non-violent.”

Gandhi’s response to Badsher Khan’s question defined the Khudai-Khidmatgar accurately, but a true understanding of the Pashtun non-violence movement only begins there.

The strength of Badsher Kahn’s Khudai-Khidmatgar and its philosophy challenged more than just the Afghan tribal code of Pashtunwali and the dominance of the British Empire in India. Badsher Khan also challenged the idea expressed by many Western orientalists that his movement was just an aberration.

As we discovered in writing our book Invisible History: Afghanistan’s Untold Story, getting an authentic picture of Afghan culture through the minefield of orientalist scholarship is no simple task. Sruti Bala’s 2013 article in the Journal of Peace and Change points out that commentaries and studies of anything regarding the Afghan non-violence movement are “ridden with interconnected problems” that make it impossible to come anywhere close to an honest understanding of Badsher Khan’s movement.

Cultural stereotyping of Pashtuns, labeling acts of non-violent resistance as simply an aberrant phase of an inherently violent culture and denying the indigenous Afghan roots of the movement are just the start. Added to that is an intellectual prejudice that privileges elitist viewpoints of Gandhi’s Hindu non-violence movement over the actual concrete acts and practices of the Muslim Khudai-Khidmatgar.

The maltreatment of the Afghan nonviolent movement reveals more about the biases of Western academics than of the movement itself and according to Sruti Bala has completely obscured its place in history. She writes:

“The social and political movement that this organization spearheaded is arguably one of the least known and most misunderstood examples of non-violent action in the twentieth century. The lack of extensive research is partly connected to the systematic destruction of crucial archival material during the colonial era, as well as by Pakistani authorities following independence.”

Why was the non-violence movement of Mohandas Gandhi awarded recognition and international celebrity status by the West; while the Pashtun Khudai-Khidmatgar movement and its leader Badsher Kahn were suppressed, imprisoned and eventually outlawed? Should the Afghan non-violent movement be dismissed as just an aberration as critics say, or is it more likely that Badsher Khan’s commitment by Pashtuns to internal tribal reform and genuine non-violent resistance was something the British Empire feared might actually change the game and so, did everything in their power to erase it from the public’s memory and pretend it never existed?

Dr. Sruti Bala provides some clues about Badsher Khan and the suppression of the Khudai-Khidmatgar. “Khan belonged to a comparatively well-off land-owning family. Unlike Gandhi or Nehru, he was neither a man of Western learning nor a prolific writer.” She writes. “In fact, he was described as, a man of very large silences,’ a nationalist leader whose life of ninety-eight years, one-third of which was spent in jail, is steeped in myth and legend.”

“Khan spent nearly thirty-five years of his life in prison for his political activities and involvement in civil disobedience actions. The British and later the Government of Pakistan systematically destroyed most documents and material records of the movement by raiding homes and confiscating anything related to the Khudai-Khidmatgar from handkerchiefs to uniforms and flags to copies of the movement’s journal.”

The treatment of Badsher Khan was an extreme example of British colonial brutality that left a mark on an Afghan society that remains to this day. But as Sruti Bala points out, without taking these aspects of Pashtun history into consideration it is easy to fall into the orientalist discourse of viewing Pashtun culture stereotypically as one that intrinsically values brutality and revenge.

According to Bala, Indian nationalism also played an important role in perpetuating the image of the brute Pashtun, while never acknowledging or mentioning its own role in sustaining a racist Pashtun narrative. As an example, the Indian bourgeoisie was quite prepared to participate in the structural and institutional violence of the Frontier Province and eager to gain favors from the British.

And then there is the Pashtun’s own complicity with the narrative through their service to the Empire. “The British ruled the Pashtun provinces through rich and influential landlords.” Bala writes. “One of the most prestigious regiments in the British Indian Army founded in 1847 was the Corps of Guides with a significant Pashtun presence. Many of the activities of the Khudai-Khidmatgar were thus addressed as much against Pashtun’s collaboration with the British, as directly against British colonial laws.

Yet without exception, the old stereotype continues to rule. Every historical account of the Khudai-Khidmatgar always begins by highlighting Pashtun culture as violent and vengeful, instead of portraying it as a culture living on the borders between civilizations under constant threat to its survival and forced to defend itself… Why is this so?

Again according to Bala, “Gandhi’s speeches to the Pashtuns on his visits to Khudai-Khidmatgar camps reveal a clear mistrust of Pashtun nonviolence which can be traced back to both a suspicion of the lower class Khidmatgar’s soldiers’ inability to embrace the ‘HIGH’ ideals of nonviolence as well as a subtle anti-Muslim slant in his perception of the Pashtuns.”

So despite overt proof of the Khudai-Khidmatgar’s commitment to nonviolence, Ghaffar Khan’s movement continued to be subjected to Gandhi’s personal mistrust of Muslim values and specifically his class biases.

“For the Khudai-Khidmatgar” Bala writes, “nonviolence was not a matter of individual soul-searching and achievement, but a principle for the entire community, requiring a collective effort. This is why I believe the Pashtun interpretation of nonviolence is very different from the individualistic approach that Gandhi adopted.”

And so in this is to be found a profound difference between the Afghan and Indian concepts of nonviolence and perhaps the key to their success or failure as peace movements. According to Bala, Khan is generally placed in the shadow of Gandhi, often referred to as his pupil or even more patronizingly as the Frontier Gandhi. They were good friends, shared similar views on civil disobedience, spent significant time working together, and held each other in high regard. But, in terms of serving as a movement whose ideals for peace could be made universal, it would seem that it was Gandhi’s appeal to the West’s upper-class elites that won him success even though Badsher Khan would have served as a more realistic, grassroots hero for a world in dire need of workable community-based formulas for peace.

Yet largely because of Gandhi, Badsher Khan’s movement remains viewed as just a poor provincial attempt at replicating his ideology and not a genuine indigenous movement of its own with its own characteristics. During his visits to the service and training camps of the Khudai- Khidmatgar, Gandhi insisted on incorporating his personal ideas such as vegetarianism, fasting, and hand spinning (Khadi) into their social reform activities in order to instill what he believed was a “true” sense of nonviolence in the soldiers of the Khudai-Khidmatgar. But for Gandhi to make his specific personal religious preferences a gauge for the purity of Pashtun nonviolence, he risked removing his philosophy from the realm of a cultural movement and placing it firmly into the realm of a personality cult.

According to Bala, references in Khan’s biography indicate that such missionary attempts at making Pashtun practices palatable to liberal upper-caste Hindu sensibilities were often met with mild derision. One Khudai-Khidmatgar leader remarked that he had no objections to eating vegetarian food in Gandhi’s ashrams, but wished the Gandhians would not be so fussy when they came to the Frontier Province themselves.

But yet, the sense of Gandhi’s moral superiority was no laughing matter when it came to the plight of the Pashtuns under British rule. In an October 1938 speech to Khudai-Khidmatgar rank-and-file members Gandhi announced openly that the Pashtun’s commitment to peace was incomplete. He then proceeded to refer to the idea that Pashtuns – who held life so cheap and would have killed a human being with no more thought than they would kill a sheep or a hen, could at the bidding of one man lay down their arms and accept nonviolence – AS A FAIRY TALE.

Gandhi made his apartness from the common Afghan man and woman, landed or landless a hallmark of his speeches. Reading them today betrays a racist sensibility and a disregard and prejudice for the detail, history, and context of Pashtun life that has been systematically carried forward into numerous current high-minded but failed social experiments.

Gandhi’s disrespect for the elaborate system of Pashtun tribal rules known as Pashtunwali is troublesome. More troublesome still is that multiple generations of historians and journalists have looked to Gandhi’s Pashtun stereotype as the end-all and be-all to the history of the Khudai-Khidmatgar. Badsher Khan understood more than anyone the need to disassemble and delegitimize the acceptance of violence within the context of Afghan society as a prerequisite for creating an authentic peace movement. It is that model inspired by Badsher Kahn that should comprise the next stage of a global movement that removes the impetus from the elite and places it in the hands of the people. And only by doing that can a genuine peace movement move forward.

Chapter 5: How JFK’s Plan for World Peace came to be

In our research into Bhadshah Khan’s Nonviolence Movement we discovered that his foundational idea was very similar to JFK’s American University speech. Rather than focusing on British oppression as the first step towards nonviolence, Khan chose to reform the ancient Pashtun tribal code that sanctioned killing to resolve family feuds. It happens that JFK promoted a similar idea. In what became known as the “Peace Speech” Kennedy asked Americans to reflect first on and reform their own concepts of peaceful coexistence before expecting the “enemy” to change.

The path that led to the creation of that Speech began with JFK’s major reason to run for president in the first place. He feared that a nuclear war could still break out regardless of world leaders’ best intentions. Within the first six months of his presidency, Kennedy’s relationship with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev had started off badly on that very issue. His impression was formed during a meeting in Vienna regarding Laos when Khrushchev was shockingly unresponsive to Kennedy’s stated concerns about the human costs of a nuclear war. JFK’s opinion changed when Khrushchev initiated a secret correspondence with him three months later in September that was kept hidden from the Kremlin due to hardliners in his government. Kennedy would soon learn that the same problem with hardliners would overtake his administration too.

Khrushchev’s first letter was 25 pages long and expressed his deep regret that distrust interfered with their ability to develop a positive working relationship from the start. The Premier compared their dilemma with “Noah’s Ark where both the ‘clean’ and the ‘unclean’ found sanctuary regardless of who is ‘clean’ and who is ‘unclean.’ The message was clear to Kennedy, either we live in peace so that the Ark continues to float, or else we all sink. Kennedy sent a letter back agreeing with Khrushchev’s metaphor emphasizing, “Whatever our differences collaboration to keep the peace is more urgent than our collaboration to win the last world war.” Thus began a very special exchange between two adversaries now becoming friends for the sake of world peace.

The first test of their evolving relationship came in October of 1961 when a standoff between American and Soviet tanks at the Berlin Wall broke out. Before rushing to judgment, Khrushchev sensed it was brought about by elements of the U.S. government without JFK’s knowledge or approval. When Kennedy did become aware of the standoff he utilized the already set up back channels to work out a withdrawal plan with Khrushchev.

But the next test was far more challenging. There were times when Kennedy had to appease the Cold War hawks around him. And one of those opportunities arose in March of 1962. Kennedy made this statement during an interview, “Khrushchev must not be certain that, where its vital interests are threatened, the US will never strike first. In some circumstances, we might have to take the initiative.” Khrushchev interpreted that last statement as a first-strike threat, which resulted in a Soviet military alert. When Kennedy’s press secretary tried to reassure Khrushchev months later, he was still not convinced and began to review his military options in Cuba. It was then decided that placing missiles would not only deter an invasion of Cuba, but it would also fix the imbalance created by the U.S. regarding its nuclear missiles in Turkey that were on the USSR’s border.

By October of 1962, Khrushchev’s decision to place missiles in Cuba became a full-blown crisis that threatened a nuclear holocaust. During the darkest moment when Soviet ships were approaching Cuba and nuclear war seemed imminent Robert Kennedy summarized his brother’s fear that the crisis would get out of his control, “What most haunted the President was the fate of all the children who’d had no say in what was happening and would have no chance to grow up and make something of the world.”

Transcripts reveal that during the crisis he was constantly being pressured to bomb and invade Cuba while catastrophic consequences were dismissed. Calls for a nuclear first strike on the Soviets continued including one meeting where his advisors causally discussed the estimated deaths of 130 million Soviets and 30 million Americans. He was so committed to de-escalating the situation; Kennedy withstood the pressure and refused to approve any of these ill-conceived plans.

The crisis finally ended after Robert Kennedy visited Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin to deliver the President’s message that his military advisors were pressing for escalation and things could quickly spiral out of control. That’s when Khrushchev ordered the Soviet ships to stop immediately in the water before breaching the U.S. blockade. Khrushchev agreed to remove the missiles in Cuba ending the most terrifying standoff of all time. Kennedy followed with a secret promise to remove U.S. nuclear missiles from Turkey that were on the Soviet Union’s border. Those missiles were removed within six months.

In December of 1962 journalist Norman Cousins asked Khrushchev how it felt to be so close to letting nuclear war break out. His response was illuminating, “I was frightened about what could happen to my country – or your country and all the other countries that would be devastated. If being frightened meant that I helped avert such insanity then I’m glad I was frightened. One of the problems today is that not enough people are sufficiently frightened by the danger of nuclear war.”

Despite progress being made between Kennedy and Khrushchev they had reached an impasse on the nuclear test ban treaty. The Soviets feared inspections were an opportunity for espionage and had agreed to three. Kennedy realized that Congress would not approve any treaty with less than eight. The president sensed that Americans had drawn the same conclusion that he and Khrushchev had from the Cuban Missile Crisis; we need to turn toward peaceful co-existence, disarmament, and cooperation. Kennedy was becoming aware that the neocons in his government would constantly undermine his peace policies. In an effort to address that fact, he asked Theodore Sorenson to write a speech that would outline his vision of peaceful co-existence. That became the basis for his American University speech in which he explained that peace becomes far more accessible when it is broken down into manageable and concrete steps, acknowledged the shared humanity of the Soviet people despite differences, and encouraged Americans to self-reflect on their own attitudes that could impede progress toward peace.

On June 10, 1963, President Kennedy delivered a speech that challenged Americans to think outside the box about war and peace and to empathize with the Soviets rather than distrust them. Kennedy had gotten word to the Soviets ahead of time that he would be giving this speech. In response, the Soviets’ allowed the full text to be published across the USSR. And that was followed by an unexpected move. After fifteen years of almost uninterrupted jamming, the Soviets stopped jamming Western broadcasts.

Suddenly the outlook for a test-ban agreement turned from hopeless to promising as Kennedy and Khrushchev agreed to the principle of inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency. This became the first nuclear treaty of the Cold War. Khrushchev then proposed that Kennedy consider a treaty banning nuclear testing in the air, space, and water, eliminating the need for inspections, as well as a non-aggression pact between NATO and the Warsaw Pact. Unfortunately, the speech was largely ignored in Washington.

Ironically one of JFK’s goals when he went to Dallas that fateful day was to condemn the notion pushed by the neocons that peace was a sign of weakness. He believed that the best way to demonstrate American strength was by being a nation striving toward peace instead of aggressive actions.” His greatest desire as president was to break the neocon ideology that has dominated Washington’s policy since the end of World War II. Whatever commitment to peace JFK brought to his presidency, it was when he and Khrushchev faced the abyss of nuclear annihilation during the Cuban Missile Crisis that sealed the deal and led to the American University speech.

Chapter 6: Passages from JFK’s Plan resonate with Badshah Khan’s message

“I have chosen this time and place to discuss a topic on which ignorance too often abounds and the truth too rarely perceived. And that is the most important topic on Earth peace. What kind of peace do I mean? And what kind of peace do we seek? Not a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war. I am talking about genuine peace, the kind of peace that makes life on earth worth living, and the kind that enables men and nations to grow, and hope, and build a better life for their children — not merely peace for Americans but peace for all men and women, not merely peace in our time but peace in all time.

Some say that it is useless to speak of peace until the leaders of the Soviet Union adopt a more enlightened attitude. I hope they do. I believe we can help them do it. But I also believe that we must reexamine our own attitude for our attitude is as essential as theirs. And every citizen who despairs war and wishes to bring peace should begin by looking inward by examining his own attitude toward the possibilities of peace, toward the Soviet Union, and toward freedom and peace here at home.

First, examine our attitude toward peace itself. Too many think it is impossible. But that is a defeatist belief. It leads to the conclusion that war is inevitable, that mankind is doomed, and that we are gripped by forces we cannot control. Our problems are manmade. Therefore, they can be solved by man. Man’s reason and spirit have often solved the seemingly unsolvable and we can do it again.

Let us focus on an attainable peace based on a gradual evolution in human institutions, on a series of actions and effective agreements which are in the interest of all concerned. With such peace, there will still be conflicting interests, as there are within families and nations. World peace, like community peace, does not require that each man love his neighbor, it requires only that they live together in mutual tolerance, submitting their disputes to a just settlement.

So let us persevere. Peace need not be impracticable, and war need not be inevitable. By defining our goal more clearly, and by making it seem more manageable and less remote, we can help people to see it, to draw hope from it, and to move irresistibly toward it.

And second, let us reexamine our attitude toward the Soviet Union. It is discouraging to read a Soviet claim that “there is a very real threat of a preventive war being unleashed by American imperialists against the Soviet Union.” It is sad to realize the extent of the gulf between us. But it is also a warning to the American people not to fall into the same trap as the Soviets, not to see only a distorted view of the other side, not to see conflict as inevitable, accommodation as impossible, and communication as nothing more than an exchange of threats.

No government or social system is so evil that its people must be considered as lacking in virtue. No nation in the history of battle ever suffered more than the Soviet Union in the Second World War. At least 20 million lost their lives. A third of the nation’s territory, including nearly two-thirds of its industrial base, was turned into a wasteland.

In short, both the United States and its allies, and the Soviet Union and its allies, have a mutually deep interest in genuine peace and in halting the arms race. Agreements to this end are in the interests of the Soviet Union as well as ours.

So, let us not be blind to our differences, but let us also direct attention to our common interests and the means by which those differences can be resolved. For our most common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.” (The full American University Speech )

Like Badshah Khan, JFK knew colonialism must end. In an exchange with Indian Prime Minister Nehru, he explained the understanding was handed down from his own family’s brutal 400-year experience with the empire in Ireland as the first colony of the British. That explains why both Khan and JFK connected to the same intuitive wisdom about creating an enduring World Peace movement. It requires this commitment, we the people must give up the use of violence from within themselves first.

Chapter 7: In order to turn from War to Peace, the Hegelian Dialectic must be dismantled

“William Roper: “So, now you give the Devil the benefit of law!”

Sir Thomas More: “Yes! What would you do? Cut a great road through the law to get after the Devil?”

William Roper: “Yes, I’d cut down every law in England to do that!”

Sir Thomas More: “Oh? And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned ‘round on you, where would you hide, Roper, the laws all being flat? This country is planted thick with laws, from coast to coast, Man’s laws, not God’s! And if you cut them down, and you’re just the man to do it, do you really think you could stand upright in the winds that would blow then? Yes, I’d give the Devil benefit of law, for my own safety’s sake!” ― A Man for All Seasons

Today’s American empire was established in the post-WWII era with the U.S. acting as “receiver” for British mercantile interests. Along with its corporate elites and imperial mandate, the U.S. inherited a 19th-century European worldview referred to as the Hegelian Dialectic, which is based on the belief that conflict creates history.

The dialectic derived from German philosopher Georg Hegel’s critique of natural law, written in 1825, in which he posited a theory of social and historical evolution. Hegel’s new manner of thinking with its Thesis – Antithesis – Synthesis revolutionized thought and served as a tool for a new breed of social engineers eager to overthrow the old world order. Hegel’s dialectics acted as the foundation for the communist economic theories of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. In essence, Hegel disputed the theory of universal natural rights espoused by other philosophers such as Immanuel Kant, thereby laying the foundations for totalitarianism. According to Hegel, human society could only achieve its highest state and mankind its highest spiritual consciousness through endless self-perpetuating ideological struggles and conflicts between bipolar extremes. This conflict of opposites when applied to social, political, and economic systems would result in the synthesizing of opposites which would inevitably lead mankind to final perfection.

Evidence of the invisible dialectic controlling the daily narrative can be found everywhere: Environmentalists against private property owners, democrats against republicans, communists against capitalists, pro-choice versus pro-life, Christians against Muslims. No matter what the issue, the invisible dialectic controls both the conflict and the resolution yet it now seems that Hegel’s progress toward perfection has led only to new and more deadly cycles of conflict. The Hegelian dialectic works as a powerful tool for legitimizing whatever dialogue advances the global elite’s interest and looking back over the past 100 years, it is almost impossible not to see how its deliberate use has created a corrupted synthesis of state power. At a micro-level, this phenomenon can be observed now taking over America’s politics.

Today’s Hegelians claim that their objective is to create a more egalitarian society. But in practice, they merely manipulate and subvert the existing order with the ultimate goal of a utopian world government i.e. “New World Order” which they themselves will rule. The system of designed social conflict to break down individual rights were spelled out by Hegel himself when he said: “‘…the State’ has the supreme right against the individual, whose supreme duty is to be a member of the State… for the right of the world spirit is above all special privileges.”’

By this definition, state power requires the rule of law, minimal corruption, judicial independence, and state monopoly over the means of coercion; as well as a political culture of some trust and compromise rather than distrust and conflict. But when the state’s monopoly on coercion ultimately leads to distrust and conflict, then Hegel’s method has reached a contradiction that it cannot escape. When democracies cling to legitimacy based solely on the use of coercion on their own citizens, they are no longer democracies but fascist/totalitarian states.

Economist and historian Antony Sutton belittled the Hegelian method by writing that at its best, “the Hegelian doctrine simply replaces the divine right of kings with the divine right of states.” So, based on America’s failures in Afghanistan and Iraq, the tumult in the Greater Middle East, and now in Eastern Europe, has the Hegelian dialectic run its course? The American empire is at a turning point politically, economically, and socially. The Hegelian dialectic of endless conflict and competition has proved ruinous to the health of Western civilization. Will its course lead to a synthesis of its best elements or into a further disintegration of what has traditionally been known as a society?

The only way to defeat the downward progression of Hegel’s hypothesis is to step outside the dialectic and free ourselves from the limitations of controlled and guided thought. By moving away from a reliance on the monopoly of coercion and reaffirming our belief in the natural rights of all humans, we will return the foundations of legitimacy to the American government. Sutton frames the Hegelian dialectic as against the spirit and letter of the Constitution of the United States by stating how “We the people” grant the state some powers and reserve all others to the people and not self-appointed elites running the State.

If Americans truly believe the rights of the state are always subordinate and subject to the will of the people and consent of the governed, and truly believe that all people are endowed with inalienable rights and are created equal, then the time has come to reevaluate the dialectic and return to our time-worn natural rights.

The West can be restored, but only if Westerners rediscover their individual human rights to those principles and traditions they claim to uphold. It is time for Western leaders to understand that the dialectic, which demands perpetual conflict, is a losing cause that has become self-defeating wherever applied. Ultimately it can only lead to self-annihilation. It is critical to establish a new and positive narrative for the American people. This is a key point in our effort to resurrect President John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s dream of world peace. We are putting JFK’s positive power to work transforming today’s toxic international scene into a movement to bring about positive change that all people around the world desperately need and want.

As difficult as it may be for Westerners to grasp, the West’s future lies in a process of re-humanization so it can address its own identity crisis. To quote from world-renowned philosopher Marshall McLuhan: “… we’re standing on the threshold of a liberating and exhilarating world in which the human tribe can become truly one family and man’s consciousness can be freed from the shackles of mechanical culture and enabled to roam the cosmos. I have a deep and abiding belief in man’s potential to grow and learn, to plumb the depths of his own being, and to learn the secret songs that orchestrate the universe. We live in a transitional era of profound pain and tragic identity quest, but the agony of our age is the labor pain of rebirth.”

We believe our future can be built based on President John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s Dream of World Peace. Doing so will promote the rights of all people around the world to move away from War to genuine Peace following its phenomenally long absence as a new standard for the West.

Introduction by Sima Wali

Guest Chapter 1

Sima Wali (4/7/1951 – 9/ 22/2017), one of the foremost Afghan human rights advocates in the world

Sima Wali was the first Afghan refugee to arrive here in 1978 hosted by former U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan, Theodore Eliot. As a cousin to the 1920s Afghan King Amanullah, Sima came with the authority of the royal family. We met her in 1998 and after asking us why the Afghan problem had gotten worse instead of better following the Soviet withdrawal in 1989 we found ourselves being drawn back into the Afghan story.

Sima’s challenge renewed our belief that something had to be done and we were soon assisting her by writing articles and speeches which she delivered to the most prestigious audiences. But despite Sima’s importance the media had no interest in the issue of Afghanistan from the perspective of the Afghan people and so began a new chapter in the saga.

In 2009 our book Invisible History Afghanistan’s Untold Story was published and we asked her to write the introduction. In a penetrating voice filled with hope and despair Sima presented her case on behalf of the forgotten Afghan people. Sima’s words reveal how her Homeland of Afghanistan was willfully destroyed by American practitioners of the Hegelian Dialectic.

Invisible History Afghanistan’s Untold Story is a phenomenal compendium of history, research, and analysis of the complex dynamics that led to the death of my home country Afghanistan—a nation as old as history itself. For Afghanistan, the aftermath of the Cold War resulted in a genocide of more than two million civilians, five million war victims, a million handicapped, and scores of internally displaced people. I had spent two decades seeking an explanation for why Afghanistan was sacrificed in the war against the Soviet Union. This book unravels that great mystery as it bears testimony for all humanity about one of the great invisible injustices of our time.